Cement history

Throughout history, cementing materials have played a vital role and were used widely in the ancient world. The Egyptians used calcined gypsum as a cement and the Greeks and Romans used lime made by heating limestone and added sand to make mortar, with coarser stones for concrete.

The Romans found that a cement could be made which set under water and this was used for the construction of harbours. This cement was made by adding crushed volcanic ash to lime and was later called a "pozzolanic" cement, named after the village of Pozzuoli near Vesuvius.

In places where volcanic ash was scarce, such as Britain, crushed brick or tile was used instead. The Romans were therefore probably the first to manipulate systematically the properties of cementitious materials for specific applications and situations.

Hadrian's Wall, a few miles East of Housesteads, England

Hadrian's Wall, a few miles East of Housesteads, EnglandRoman contribution to cement technology

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, a Roman architect and engineer in the 1st century BCE wrote his "Ten books of Architecture" - a revealing historical insight into ancient technology. Writing about concrete floors, for example:

"First I shall begin with the concrete flooring, which is the most important of the polished finishings, observing that great pains and the utmost precaution must be taken to ensure its durability".

"On this, lay the nucleus, consisting of pounded tile mixed with lime in the proportions of three parts to one, and forming a layer not less than six digits thick."

And on pozzolana:

"There is also a kind of powder from which natural causes produces astonishing results. This substance, when mixed with lime and rubble, not only lends strength to buildings of other kinds, but even when piers are constructed of it in the sea, they set hard under water."

(Vitruvius, "The Ten Books of Architecture," Dover Publications, 1960.)

His "Ten books of Architecture" are a real historical gem bringing together history and technology. Anyone wishing to follow his instructions might first need to find a thousand or so slaves to dig, saw, pound and polish...

After the Romans, there was a general loss in building skills in Europe, particularly with regard to cement. Mortars hardened mainly by carbonation of lime, a slow process. The use of pozzolana was rediscovered in the late Middle Ages.

The great mediaeval cathedrals, such as Durham, Lincoln and Rochester in England and Chartres and Rheims in France, were clearly built by highly skilled masons. Despite this, it would probably be fair to say they did not have the technology to manipulate the properties of cementitious materials in the way the Romans had done a thousand years earlier.

Cement history and the Industrial Revolution

The Renaissance and Age of Enlightenment brought new ways of thinking which led to the industrial revolution. In eighteenth century Britain, the interests of industry and empire coincided, with the need to build lighthouses on exposed rocks to prevent shipping losses. The constant loss of merchant ships and warships drove cement technology forwards.

Smeaton, building the third Eddystone lighthouse (1759) off the coast of

Cornwall in Southwestern England, found that a mix of lime, clay and

crushed slag from iron-making produced a mortar which hardened under

water. Joseph Aspdin took out a patent in 1824 for "Portland Cement," a

material he produced by firing finely-ground clay and limestone until

the limestone was calcined. He called it Portland Cement because the

concrete made from it looked like Portland stone, a widely-used building

stone in England.

While history usually regards Aspdin as the

inventor of Portland cement, Aspdin's cement was not produced at a

high-enough temperature to be the real forerunner of modern Portland cement. Nevertheless, his was a major innovation and subsequent progress

could be viewed as mere development.

A ship carrying barrels of

Aspdin's cement sank off the Isle of Sheppey in Kent, England, and the

barrels of set cement, minus the wooden staves, were later incorporated

into a pub in Sheerness and are still there now. Those who wish can sup a pint and contemplate cement history.

A few years

later, in 1845, Isaac Johnson made the first modern Portland Cement by

firing a mixture of chalk and clay at much higher temperatures, similar

to those used today. At these temperatures (1400C-1500C), clinkering

occurs and minerals form which are very reactive and more strongly

cementitious.

While Johnson used the same materials to make

Portland cement as we use now, three important developments in the

manufacturing process lead to modern Portland cement:

- Development of rotary kilns

- Addition of gypsum to control setting

- Use of ball mills to grind clinker and raw materials

From the turn of the 20th century, rotary

cement kilns gradually replaced the original vertical shaft kilns, used originally for

making lime. Rotary kilns heat the clinker mainly by

radiative heat transfer and this is more efficient at higher

temperatures, enabling higher burning temperatures to be achieved. Also,

because the clinker is constantly moving within the kiln, a fairly

uniform clinkering temperature is achieved in the hottest part of the

kiln, the burning zone.

The two other principal technical

developments, gypsum addition to control setting and the use of ball

mills to grind the clinker, were also introduced at around the start of the 20th century.

An entire website could easily be devoted to the history of cement, but this brief introduction may suffice to place cement in a historical context.

Check Out the Understanding Cement Resources!

We have some great training and reference resources. Some are free and some are paid-for.

The paid-for resources are unique to Understanding Cement and proceeds from these sales contribute to the costs of operating and developing this website - see our bookstore here.

The free resources are available on the Cembytes Resources Page. Currently, they include:

Ebook: "Low Concrete Strength? Ten Potential Cement-Related Causes": this illustrated ebook is a checklist of some of the main causes of cement-related low strength in concrete or mortar.

Cement glossary: glossary of over 100 cement-related definitions and chemical formulae.

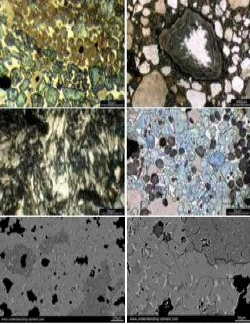

Screensaver/desktop images: six microscope images of clinker and concrete that you can use as desktop/tablet or screensaver images, or anything else you want.

Subscribers to Cembytes, our free Understanding Cement Newsletter, can download these free resources from the Cembytes Resources Page.

If you are not already a subscriber, just sign up using the box below and you can be downloading the ebook, glossary and photos within a minute or two. Make sure you bookmark the resources page so you can get back to it later - there are no links to it from the website navigation as it is for Cembytes subscribers only!

If you are already a subscriber to Cembytes, you can access the Cembytes Resources Page directly if you have bookmarked it. However, if you have forgotten how to reach the Resources page, you can easily get back to it. Just enter your email in the signup box below and if you are on the subscriber list you will see a link to the Resources Page.

(Note: we currently have two Cembytes subscriber lists, and old one and a new one, and we are gradually transferring to the new one. Depending when you subscribed, you will be on one list or the other. If you are on the old list, the signup box won't recognize you because it is only connected to the new list, but that's fine. Just confirm your subscription and you will be on the new list. After you confirm you will receive an email with a link to the Resources Page.)

Get a Better Understanding of Cement

Articles like this one can provide a lot of useful material. However, reading an article or two is not really the best way to get a clear picture of a complex material like cement. To get a more complete and integrated understanding of cement and concrete, do have a look at the Understanding Cement book or ebook.

This easy-to-read and concise book contains much more detail on concrete chemistry and deleterious processes in concrete compared with the website.

For example, it has about two-and-a-half times as much on ASR, one-and-a-half times as much on sulfate attack and nearly three times as much on carbonation. It has sections on alkali-carbonate reaction, frost (freeze-thaw) damage, steel corrosion, leaching and efflorescence on masonry. It also has about four-and-a-half times as much on cement hydration (comparisons based on word count).

Click here for more information

Check the Article Directory for more articles on this or related topics